Everybody dreams about reinventing the past.

I’m a technologist, and I sometimes (often) I like to think about how some basic technologies could look, if we knew then what we knew now. When a technology is ubiquitous, or even just successful, it’s easy to take for granted the warts in its design, or the tradeoffs that were made at the time. So it can be illuminating (and fun(!)) to think about how things could have been different.

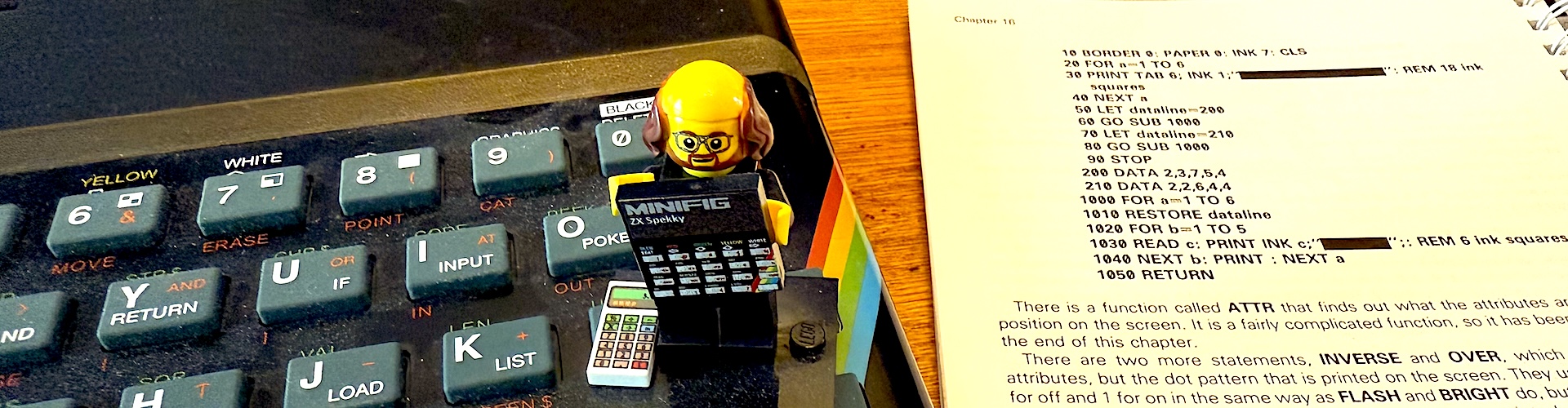

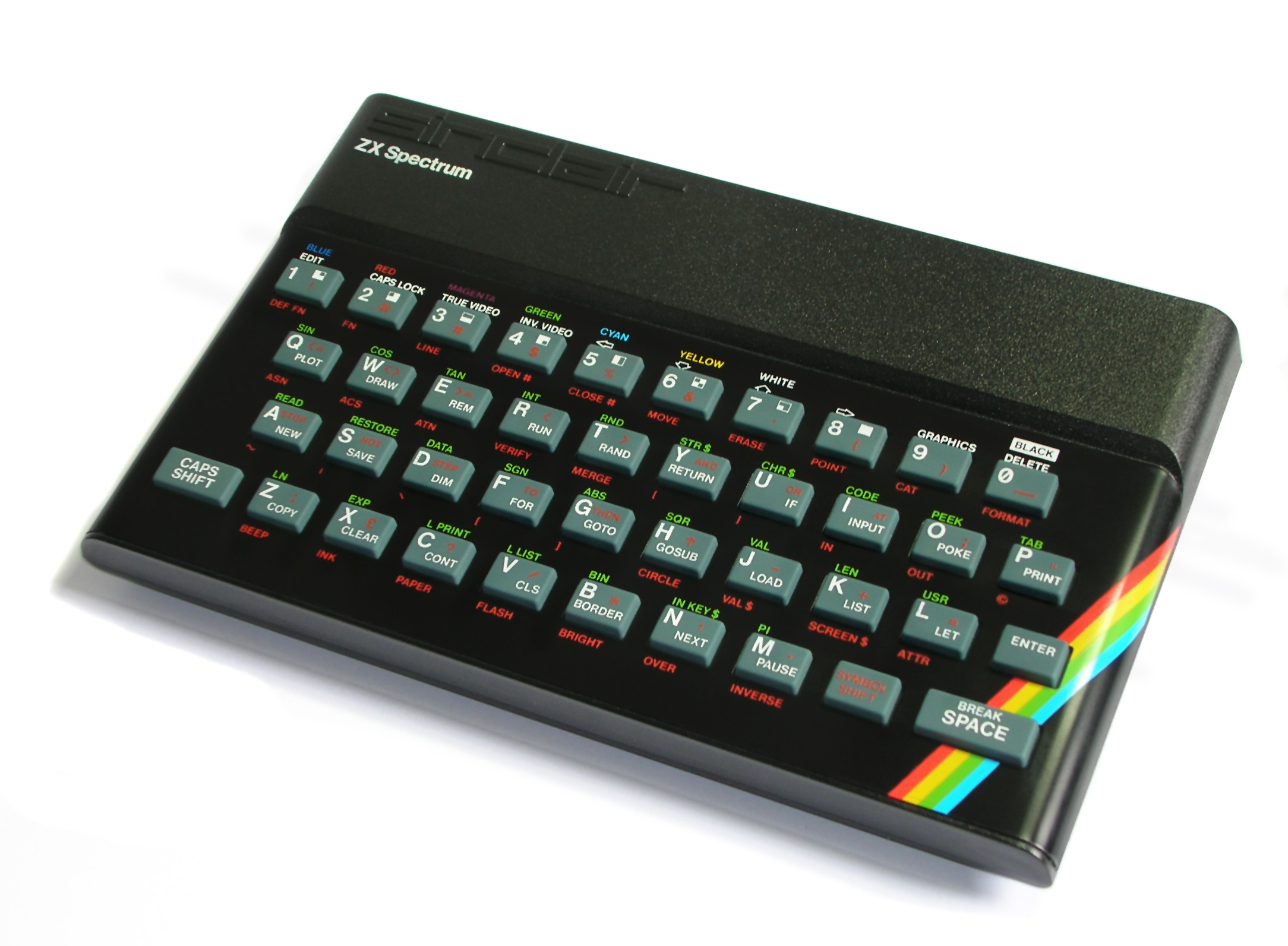

This post introduces a project of mine to perform some surgical technological revisionism on a 1982 home computer icon: the Sinclair ZX Spectrum.

The Sinclair ZX Spectrum

In the early 1980s, in the UK, there was a microcomputer boom; a Cambrian explosion of 8-bit possibilities. (In 1981, our family bought a Sinclair ZX81, and I learned how to program. Then I got a ZX Spectrum.)

There were loads of games for the Spectrum, load of magazines devoted to the Spectrum, and it left an indelible mark on the UK computing scene. The ZX Spectrum, even today (2025), has a massive retro computing following. Only a year or so ago (2024) a new incarnation of it was released—The Spectrum—and enthusiasts still continue to release new games continue for this ancient, 40-something, computing platform.

The ZX Spectrum was launched in 1982 as a ‘home computer’, which in the 1980s meant:

- In practice, it was really a games device, competing for space on the family television, and played by the kids. Games were loaded via audio cassette tape: most households of that era had a portable cassette recorder which could be used to load and save programs.

- Some of these kids learned how to program, by typing in listings from computer magazines, or from reading the many books which were published. Almost every home computer in the 1980s had a version of the programming language BASIC.

- The advertisements for home micros all claimed that the family could use their new computer to balance the household expenses, run a business, do school homework, and do many of the things that now people use PCs or Macs to do. Perhaps a few people did, but not many.

Importantly, home computers, and the ZX Spectrum were amazingly successful. The Spectrum doesn’t need me to reinvent it to (retospectively) make it more successful.

What if

But, given 40 years of advances in programming languages; the art of User Experience; computer graphics & typography, looking back at old technology often makes me think: ‘What if the creators of this technology knew then what we know now?’

The Spectrum hardware design is remarkable: the engineers achieved a colour computer, with audio, and fast (ish) performance for a very low manufacturing cost, which could be sold very cheaply. And its industrial design is beautiful. These are probably the main reasons it was one of the most popular home computers of the era.

However, it was developed under great time pressure, and to be manufactured cheaply, it was heavily based on Sinclair’s previous home computer, the ZX81. There were a lot of loose ends and short-cuts in the ROM code. But, honestly, the magic of a little box that could make colour images and sounds, and play games, was astonishing enough.

In terms of the software:

With any technology, over time, people discover ways to eke out more performance, or do things that the technology was not designed to do. They discover optimisations, and share tricks. Today, 40 years after the Spectrum’s original launch, we’re seeing games for it, which display more colours on the screen, or have smoother animation, than ever thought possible at the product’s launch.

And the last 40 years have seen a seismic shift in how we relate to computers—what we expect from them, and the programming algorithms discovered in the meantime that we can use on them. ’80s micros were marketed as tools to learn how to program. Programming pedagogy and practice is very different nowadays than it was then.

In particular, the programming paradigm promoted by BASIC is horribly archaic. We call its coding style now ‘spaghetti coding’—a jumbled mess. Even in the early 1980s, late 1970s, better alternatives—structured coding and Object Oriented programming—were being developed. BASIC does not teach good (nor modern) practices.

And BASIC is easy to start using, but it does not lend itself to composing larger projects.

It’s also very slow, having been optimised for ease of implementation. Sinclair BASIC was originally designed to fit in the tiny Read Only Memory (ROM) of the ZX81, which lead to some significant compromises.

As a software designer, it’s very tempting to imagine rewriting it.

So just what could have been possible?

Side note: the role of the Spectrum ROM

Just a side note to point out that the Spectrum ROM is very well-suited to such a reimagining: The ZX Spectrum was designed to be very cheap to manufacture, and one aspect of this was that the hardware was as minimalistic as possible. As far as possible, features were implemented in the ROM software instead of in (expensive) hardware.

The simplicity of its hardware design possibly contributed to its flexibility and longevity, and, by replacing the ROM, we can change almost the whole character of the machine.

I implied that this project is about reimagining a 1980s computer, but really it’s about reimagining its ROM firmware layer, leaving the hardware unchanged.

There is one aspect of the hardware I’d change: I’d remove the hardware capability to flash blocks on and off, on the screen, and replace it with a little more flexibility to display colours. But we’ll leave that til later.

What started this idea

I don’t honestly know. A large part is probably the fact that my own children are approaching the age I was when I first discovered these Sinclair computers.

In any case, in February 2024, slightly bored with my day job, I started inadvertently obsessing about how the Spectrum ROM software could have been better designed. Something grabbed my brain and would not let go. I was particularly worrying away at two questions:

- Could it be possible to design a built-in programming language that was simultaneously: more memory-efficient (allowing larger, more complex user programs), and faster to execute, and clearer and easier to learn, than ZX BASIC? I thought I had a design that might work.

- The built-in Spectrum commands for text, graphics, sound, and everything else have since been greatly improved upon by others:

- Drawing lines and circles should be about 20 times faster than the existing Spectrum ROM.

- Tape loading routines could be about 50% faster

- We could include some useful building blocks for writing games—because all the kids in the ’80s wanted to write a computer game—like simple sprites and screen-scrolling.

- Could the built-in Spectrum software look…well… prettier? Not just prettier, but also more approachable; more productive; easier to use. Importantly, it should be approachable for beginners, while offering a smooth ramp to more advanced use.

- The on-screen typography could be easier to read, making programs easier to read, and potentially allowing editing code with syntax-highlighting.

- Modules? A way of taking bits of program published in magazines, or on tapes and integrating them into your own program.

- Some sort of way of disassembling machine code, or even assembling it. That would only be for advanced users, but, again, helps provide a more gradual on-ramp to advanced usage.

I thought we could take some of the modern affordances that 2020s software developers take for granted, and take them back to the 1980s.

Nine Tiles

The Spectrum ROM was originally designed by Steve Vickers & Richard Altwasser of Nine Tiles, in 1981. Steve Vickers also wrote the user manual. I do not want to diminish their achievement!

I think we can do better, but I have several advantages over the original ROM developers: I have their design to jump off from. That original version—and the Spectrum hardware itself—is now exceptionally well documented online. I have all the resources of today’s retro-programming scene to use as reference too, and I have the benefit of hindsight. They were working to a tight deadline; I am not.

And I have access to much more sophisticated software engineering tools (editors, source control, debuggers) than they did.

Journey of 1000 miles, etc.

So I started by redesigning the Spectrum font…

Hey, you have to start somewhere.

To be continued…